University News

A Tale of Two Papers

October 16, 2018

To celebrate the recent National Newspaper Week ....

From the Summer 2017 issue of Western: The Magazine for Alumni of Western Illinois University

By Darcie Dyer Shinberger '89, MS98

---

Like Charles Dickens wrote: "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times."

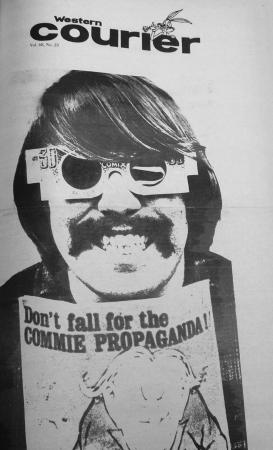

The Vietnam War, Kent State, conservatism and pro-war versus liberalism and anti-war, hippies, Nixon and more ... the late 1960s and early 1970s were rife with controversy, conflict and chaos. And the campus of Western Illinois University—a microcosm among the cornfields—began to reflect what was occurring throughout the world. With protests taking place, an "us versus them" mentality taking hold and an administration that was attempting to keep its thumb on the student body, a group of WIU students took to the pages of the Western Courier to share their opinions of the war, the presidents (U.S. and University) and the faculty, along with news that many considered "left wing."

That "liberal approach" eventually led the Courier to be kicked off campus, and to the creation of a more conservative newspaper, the Western Catalyst. The Catalyst, run by former Courier editor Rick Alm, and later by John Maguire ‘73, reported the "straightforward" news the journalism faculty and administration agreed represented Western.

Thus begins the "tale of two papers."

Divergence, Deviance, Diversity & Disestablishment

Paul Reynolds was the Courier's editor from 1968-69. An outspoken anti-war activist (and editor of Western's first underground newspaper, the Mae West) "shook Macomb as it was never shook before." [from the 1973 Sequel, "Revolution at WIU Revisited," by Dennis Hetzel ‘74, who joined the paper as a freshman in Fall 1970 and took over as editor of the Courier in 1972]. When Reynolds was awarded the editorship, the Courier was beginning to be considered a "radical" newspaper.

According to Hetzel, while President John Bernhard supported freedom of speech and freedom of press, he was coming under intense pressure from alumni, legislators, Board members, community members and parents for the content of the Western Courier. Laden with profanity and anti-war rhetoric, along with highly political (and sometimes personal) editorials, the Courier was considered very controversial, Hetzel remembered.

"We resent the one-sided, left-wing, reactionary and revolutionary policies of Paul Reynolds and his staff ... this paper is a travesty," one letter stated. The father of a female student wrote to President Bernhard, "I object strenuously to the publication of a condom advertisement ... I can use dirty language as well as the next guy, but must we subject college students to gutter lingo."

"You have to remember during this Vietnam-era, it was a sensitive, volatile time. There was a lot of anger from both sides. The Courier did have a left-wing, anti-war posture and that was not popular among a lot of people," Hetzel recalled. "But President Bernhard wasn't the villain here. He was trying to herd cats, and he was under an enormous amount of pressure. This was a very controversial newspaper, with obscene language and a very alternative approach."

Looking at the Courier's "journey" to the "radical" student newspaper of the late 1960s through early 1970s, Reynolds, who was a student at WIU from 1967-71, was first part of the Courier's staff under the leadership of Alm.

"The Courier was a moderate conservative newspaper. It was a time of a small school of journalism led by faculty who were stuck in the 1950s. The change in content started when the communication students and faculty selected me as editor," Reynolds explained in a recent interview. "I was far left when I was appointed, so it should have come as no big surprise that the paper would go in that direction of progressive and anti-war."

While the Courier was still housed in the University Union with Reynolds at the helm, he has no doubt that he played a role in the displacement off campus, which Dave Huey, who took over as editor, navigated, Reynolds said.

"Right after the [post-1970 Kent State shootings] takeover of Simpkins Hall, President Bernhard called me into his office. It was a tense time on campus, and there was a lot of turbulence, but I think he really supported our right to say what we thought and what we felt. He was under a lot of pressure because of what we were publishing. He told me ‘I wish you wouldn't be so glandular,'" he remembered with a laugh. "What's funny is even though we were considered far left by conservatives on campus and in the community, there were some that still thought we were still too normal or in the middle. We covered Greek news, sports and the usual. We felt a responsibility to cover the news, but would we go out to lunch and go over the edge? Yes. We were by far not the most radical, but we were in front and we were unabashedly anti-authoritarian. We felt we had a responsibility to cover what was happening on campus and around the world."

While the newspaper took a decidedly left stance under his direction, Reynolds added he is proud of what the paper stood for. It supported diversity, and women and minorities were hired at the Courier at a time when both groups weren't given much in the way of opportunity to voice their opinions.

"They had the freedom to do what they wanted, and we helped motivate them and we supported them," he recalled.

Huey's sister, Pam '72, started with the Courier during her freshman year, covering student government and other stories. She went on to enroll in Paul Simon's master's degree program for journalists at Sangamon State (now UIS), and worked for the Associated Press, United Press International, and now is an editor for the Minnesota Star Tribune. Nate Lawrence was the first president of the Black Student Association (BSA) at Western and he was also the Courier's first Black columnist.

"We started the BSA because we weren't being well-served, and that of course, is what also prompted me to join the Courier staff. There were no other avenues for our issues and our school of thought, but the Courier provided that access and provided a forum to share what Black students on campus were experiencing," Lawrence said. "The climate of campus, as it was, there were no ‘yellow brick roads,' so to speak, for Black students. Like Bill [Knight] '71, Paul and others who took more of the ‘anti' posture, we felt underserved and disenfranchised either because of our long hair, our beliefs or our skin color, so it was a natural match for us to come together. Their issues were our issues."

Lawrence said one of the things he is most proud of is through his work at the Courier and his group's outspokenness, the flunk-out rate among Black students ceased.

"Nobody had a solid grasp about what was going on on campus. There were no resources for us and we were not advised what to do to succeed.

The Courier allowed us to bring to light what was happening to this core group of students," he added. "The collaboration of our group and other groups of ‘misfits' was perfect. It was functional and it was effective."

Prior to joining the Courier staff, Lawrence worked for Reynolds' underground newspaper (the Mae West). When Lawrence was with "the West," he actually called for a boycott of businesses due to the way Black students were treated by some merchants.

"This gave me my first insight to the true power of the press," Lawrence said. "I'm proud of the work we did. No one was buying the BS from politicians and others, and we were able to bring to light a lot of issues."

Reynolds added because of the diverse nature of not only the staff of the Courier, but also the content, he believes they motivated the student body to take a more active role on campus.

"We had more than 1,000 join us in an anti-war march from campus to the downtown area," Reynolds recalled. "We actually had a lot of support from the student body."

But it wasn't the student body that was complaining to University administration about the newspaper's content. Hetzel recalled how, when he was a part of the staff, they couldn't unload the papers fast enough on campus as people were waiting to grab them literally hot off the press. Still, it was Reynolds' and his staff's forward thinking—and pressure from those who held the power—that led to the Courier moving off campus and forming the corporation Bitter Carrot, LLC, with Huey eventually at the helm.

Reynolds added that he didn't think it was any "one thing" or the proverbial straw that broke the camel's back that led to the "dismissal" of the paper to off-campus premises.

"Do I cringe when I go back and read what I wrote, sure. I know we rubbed people the wrong way, but at the time, it was relevant. It was political," he said. "I understand now that the powers-that-be had to show some strictness, and if I had to do it over, I may have done things a bit differently. Really, the only remorse I ever felt at the time was that I wasn't a bigger help to Dave when he became editor and had to navigate the paper off campus. But Dave is the strongest, most salt of the earth, man I know, and Bill (Knight) was a strong leader as well."

Huey joined the Courier staff in Summer 1969, after a four-year stint serving on U.S. Navy submarines. His sister was at WIU, he had spent four years on subs, and he was newly married and trying to decide what to do. At his sister Pam's urging, Huey and his wife, Marcia, moved to Macomb. He first worked at Edison Porcelain while attending school, but then a fellow classmate, Greg Norton, told Huey about the Courier seeking new writers.

"That was when I met Paul. He hired me and we got along well, but he was the rabble-rouser," Huey laughed. "I was the quiet guy in the background when I was hired, and we played good cop-bad cop well, but really the seeds of activism had already been planted in my psyche when I was in port during the Fall 1968 Democratic Convention. I was watching on TV how kids like me were being beaten by Chicago cops and given the okay by Mayor Daly to do so to ‘preserve order.' By the time I enrolled at WIU the next year, those seeds were in full bloom. I started hanging out with people who believed in the same things I did, and it was just a natural evolution the more I was exposed to what was going on."

By Fall 1969, Huey was the assistant editor, and during the 1970-71 academic year, he assumed the editorial-ship. The Courier was still housed in the Union, but there were continued rumblings about the University's liability in regard to the ongoing controversial content appearing each week. Huey echoed Hetzel's and Reynolds' sentiments that it was a "tumultuous time."

"There were demonstrations on campus, and there was a group that took over Simpkins Hall* where ROTC was housed, for three or four days," Huey recalled. "We coordinated the coverage and we had some pretty flamboyant coverage." [*Editor's Note: See Blast from the Past on page 8 for more on this event.]

That flamboyancy was apparent with the very first issue of the Fall 1970 newspaper when the front and back of the newspaper was designed to look like the cover of Zig Zag rolling papers, complete with a light screen at the top of the inside pages to replicate the adhesive.

"It looked like you could roll it as one big joint. There was a lot of consternation about that particular Welcome Back issue, and we reveled in being troublemakers" Huey said. "That's how my editorship started."

The Winds of Change (or "Hydroplaning Off Campus")

It was also that year that an accident changed Huey's course. On Feb. 4, 1971, he was on his way back to Macomb in his Plymouth station wagon, loaded with 10,000 freshly printed Couriers from Martin Printing in Havana. It was sleeting and his mind was elsewhere, thinking about how he had to get back with the papers. He passed a semi, and in the sleet, didn't see another one coming straight at him on the rural two-lane highway. Huey sped up to get around the semi to avoid a head-on collision and as he navigated back onto the right side of the road, he lost control of the car. Huey was quick to point out that he was not stoned at the time, just inexperienced driving in the central Illinois winter weather.

"This was my first introduction to hydroplaning. The last thing I remembered was seeing utility poles as I went off the road and driving right into one. My face hit the steering wheel so hard that the steering wheel was unrecognizable. Yet, I was out of the car, picking up newspapers while my blood was dripping everywhere. I guess I was in shock," he said.

He ended up in the ICU, having broken every bone in his face. Huey was out of commission until at least the first part of April. George Taft '72 took over for a brief period as editor until Hetzel took over the role of editor in 1972 (Taft later went on to launch SunRise Magazine with Bill Knight and Mike Mooney). It was during Huey's recovery that Bernhard succumbed to the pressure and the Courier was removed from campus.

However, despite being kicked off campus, the paper continued to receive student fees to operate after a referendum overwhelmingly passed, the student body supporting the Courier. The merry band first moved to an old house near campus, where Hetzel said there were so many code violations, he's surprised they never fell through the floor. Eventually, the newspaper offices made its way to the Macomb Square, taking up residence on the second floor of the donut shop (where Sullivan Taylor now resides). Huey added that Gary Tagtmeier, his "frat boy business manager," was invaluable in keeping the paper together financially. He, along with his fraternity brothers, made sure the checks didn't bounce, and Neil Stegall, who was Courier columnist, was elected as the student body president, with the support of the paper.

"Neil was our heart and soul and was instrumental in passing the referendum that kept student fees coming to us. Yes, we were a leftist rag, but we were also the merry pranksters," Huey recalled. "And to protect us, and to protect the University from liability, with the help of Art Greenburg, an ACLU attorney from Peoria, who worked for us pro bono, and WIU Librarian Lois Mills, the Courier incorporated as Bitter Carrot, LLC. Art and Lois were an enormous help and really supported us. While Ms. Mills surely didn't approve of all the content of those Couriers, she was prepared to defend fiercely students' First Amendment right to make the content decisions. Lois was a friend and mentor from day one; she was a hell of a woman."

Reynolds added that Mills "was a saint in all of this as she really helped us navigate the move to a corporation, and as a liberal herself, she really believed in and supported us."

Huey left the Courier and Bitter Carrot in August 1971, after the birth of his daughter. His wife had returned to North Dakota, and Huey chose to follow to continue his education in North Dakota, rather than continue "rabble rousing" in Macomb. Hetzel remained at the helm and continued the paper's tradition.

"Those student fees were our lifeline. It kept the Courier going," Hetzel said. "But when we were removed from campus, they literally took every desk and filing cabinet. We found that house first, and then moved to the square, and we managed to put a paper out every week. We had light tables, a dark room, typewriters, anything we could cobble together and a pop machine that dispensed beer. And the only printer that would print our paper was Martin Publishing in Havana, so we would run the paper to Havana late into the night, wait for it to be printed and drive it back to Macomb. It was an intense time, but it was an exciting time. There wasn't just a divide on campus, but in the journalism world as well with the birth of Rolling Stone and Hunter Thompson. It was new journalism.

"Looking back now, we weren't really worried about the future of the paper, or if we were loved or hated on campus. I will tell you this though: people loved to read the paper and they looked forward to it. Amazingly, we were still allowed to deliver it to campus and people would be waiting for it," he added. "While we had some intense stuff in the paper, we had a sense of fun with it too. We had some crazy stuff that made it a fun read. Joe Layng and other members of the SGA were enamored with Buckminster Fuller, the architect who came up with the geodesic dome, so on Halloween, we printed the paper on orange paper and had a geodesic Jack-O-Lantern as the center spread. People looked forward to reading this beyond the sociopolitical news."

Fake News, Fun & Feebs

Hetzel also remembered one week when there was a hole in the sports section that needed filled, they came up with the fictitious WIU Pinball Team, "The Steelballers." T-shirts were made, they had team photos taken and had stories about the "team's" rousing success, beating other "teams" throughout the nation.

"Today it would be called fake news, but back then it was a parody of the clichéd jock sports features," he laughed. "And the creation of this team and these stories was a success. Papers today have lost this sense of fun."

It was that sense of fun and political activism that drew Bill Knight to the Western Courier and Bitter Carrot, LLC. The English major from Hancock County started working at the Courier under Huey's leadership in 1970 and was part of the move off campus.

"It was a rude awakening for us. From a corner office in the Union and having our equipment provided, to cobbling things together," Knight said. "But we didn't care where we were. It was a challenge, but it was fun and we learned a lot on our own."

Knight recalled that those faculty and community members who supported the Courier kept their heads fairly low and didn't actively voice their support, outside of select faculty and staff, like Mills, Don Daudelin '72, Yale and Ann Sedman, Norman Anderson, Clifford Johnson and James McKinney.

"We did have encouragement and support from a surprising amount of people, but most of them kept pretty quiet about it," Knight said. "The paper under Paul's leadership first was a stark contrast to what most were used to and it was a shock to many, but we kept it going. And despite what may have seemed like a bunch of troublemakers running the paper, we actually became more professional in terms of meeting deadlines, selling ads, budgeting and running things. We even had a business editor. It was a practicum in a sense."

One of those "big practicum" moments Knight remembers is when he and Mike Mooney were paid $50 each in 1972 to attend and cover the Democratic and Republican conventions in Miami, FL. Because $50 was a lot of money to a college student, the pair pocketed the money and hitchhiked to Florida ... both times. In addition to running the newspaper, Bitter Carrot also branched out to other ventures, such as concert promotions, band posters and more to add to their source of revenue.

"I actually think getting kicked off campus was a blessing in disguise now that I look back. We learned so much ... we developed our skills from zero. Yes, the funding was still there from the student body thanks to the referendum, but there was absolutely no more illusion that Big Brother was watching our every move and we could make this our own," he added.

While the University's Big Brother wasn't necessarily watching the group off campus ... a much larger organization was keeping its eye on the Courier and some of its staff. Knight, Hetzel, Reynolds and probably a few others had FBI files as a result of their activism and outspokenness during those years.

"I'm sure I have an FBI file that's two feet thick, and it's probably a fun read," Reynolds laughed. "I'm sure they're pretty surprised that so many of us went on to be quite successful. Our mental DNA was great."

Huey added that shortly after he returned to North Dakota, two men who looked like "buff Blues Brothers" entered his place of employment and asked to speak with him.

"They flashed FBI badges and scared the sh** out of me. I showed up at noon for the interview, and they asked me ‘What do you know about the White Panther Party to blow up the CIA HQ in Langley?' I burst out in laughter, more from nervous relief than anything else. The White Panthers were Bill's (Knight)bailiwick. I knew nothing. I saw nothing. I only wrote their press releases," Huey chuckled.

Knight and Hetzel have their redacted FBI files in their possession, and Knight remembers one of their staff members was actually picked up by men in a black sedan as he walked down Adams Street, driven to Peoria and indicted in federal court for draft evasion.

"It's really chilling that they knew so much about us, but it's even more shocking that they (the FBI) had so much wrong, as well," Knight said.

The Catalyst

While there was a sense of fun intermingled with the social commentary (and cuss words), there were still a number of journalism students who wanted the more "traditional" clips for their portfolios, and thus, The Catalyst was established, so from 1969-74, WIU had two student newspapers. While The Catalyst didn't receive student fees, but it held its own thanks to the community advertisers who didn't want to be associated with the Courier and Bitter Carrot productions.

According to "First Century: A Pictorial History of Western Illinois University" by English Professor Emeritus John Hallwas '67 MA '68, many local people, at WIU and in town, supported The Catalyst. The chief figure behind the newspaper was (Rick) Alm, but soon the Maguire brothers took over: George was the business manager, while John Maguire, who started as a sports writer, soon became managing editor and later, the editor.

"I'd describe the two papers as one, The Catalyst, was traditional journalism, while the Courier was a more social justice, activist journalism and they were very good at it. The Courier was the anti-Fox News of the 60s and 70s," (John) Maguire ‘73 said. "But there were a lot of journalism students who could not or would not work for the Courier. They wanted clips that weren't anti-establishment, and The Catalyst helped provide those traditional stories. But really, the Courier was ahead of the curve in its commentary."

Maguire added that President Bernhard was the right president during a time of unique transitions taking place, but the pressure from others that forced his hand to move the Courier off campus also allowed for the creation of the "underground" Catalyst.

"That pressure translated into paid advertising for us, which allowed us to print as a traditional publication, which is what many community members and others seemed to want," he explained. "People who advertised with us didn't want to be under a column or story that went against their personal beliefs, so it worked well for us.

"And we weren't antagonistic toward our counterparts, we just wanted something for our resumes that matched up with mainstream media, because much of that was not anti-war," Maguire said. "

Knight added that there indeed was no professional animosity between the staff at the two newspapers.

"I think we were bemused by each other," Knight laughed. "And we were friends with a lot of them."

While the content of the two papers varied, what was similar was that neither paper was on campus. The Catalyst used the office of the Business News, which was an independent shopper that was run out of a house on Edwards Street.

"We rented locker 662 in the Union so people could drop off their stories and story ideas to us on campus," Maguire said.

Two Minus One = One

In the mid- to late-1970s, the editorial-ship of both papers changed, and it became apparent to the editors and the staff of both papers that two newspapers were no longer necessary, so the Courier and The Catalyst merged into the Prairie Star.

While it was the official student newspaper of Western Illinois University, it remained off campus, above the donut shop until the 1980s. Administratively, the newspaper returned to campus, in 1983, but was allowed to stay above the donut shop for a one-year grace period to "give them time to adjust to their impending return." In June 1983, Vice President for Student Affairs Ron Gierhan sent a letter to Courier Editor in Chief Glen Ponczak informing him of the decision to allow the paper back on campus.

One year later, Terry Lawhorn '71 MA '73 was hired as the adviser to fully assimilate the newspaper back into its on campus digs, the Heating Plant Annex (where the Courier remains today). Lawhorn served as the newspaper's adviser until his retirement in June 2005, after 21 years.

Final Footnote

"The Courier and everyone I worked with and met through that experience is one of the most important experiences of my life," Hetzel concluded. "If I hadn't have gone here and hooked up with these crazy people, I'd have a much different life today. And to the students at the Courier now ... you work for one of the most interesting student newspapers in the nation, historically speaking. Those were some crazy times."

Posted By: University Communications (U-Communications@wiu.edu)

Office of University Communications & Marketing

Connect with us: